- Industries

Industries

- Functions

Functions

- Insights

Insights

- Careers

Careers

- About Us

- Sustainability

- By Omega Team

The Amazon rainforest is a large biome that spans South America. The Amazon basin covers an area of 26m square miles and accounts for 40% of South America, more than half in Brazil. At 3,977 miles long, the Amazon is the second-longest river in the world after the Nile. It is the world’s largest river by volume, accounting for 20% of the world’s river flow. The Amazon basin contains an abundance of natural resources. Its rainforest area accounts for 1/3 of the world’s rainforest area and 20% of the global total forest area. It is also known for its high biodiversity – about a tenth of the earth’s species are found in this area.

Global Deforestation Issue Overview

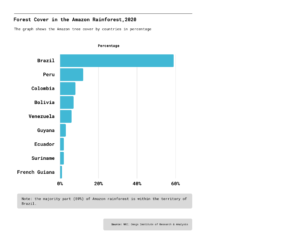

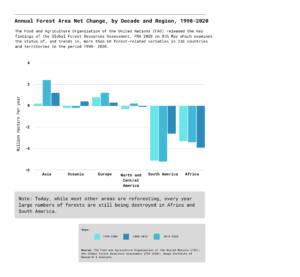

The Amazon rainforest covers a huge area mainly in Brazil but also Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, French Guiana, Guyana, Peru, Suriname and Venezuela. Figure 1 shows the tree cover of each country. It is the treasure of all mankind, and it is the common responsibility of humans to protect it. Yet the world’s forests, including the Amazon rainforest, continue to be threatened. The world has lost 178 hectares of forest since the 1990s. The rate of net forest loss declined from 7.8 million ha per year in the decade 1990–2000 to 5.2 million hectares per year in 2000–2010 and 4.7 million ha per year in 2010–2020. The rate of decline of net forest loss slowed in the most recent decade due to a reduction in the rate of forest expansion.

As can be seen from figure 2, in some continents such as Asia and Europe, attention has been paid to the protection and restoration of forests and certain positive results have been achieved, especially in some Asian countries such as China and India. In contrast, forests in South America and Africa continue to be heavily threatened. In South America, annual forest loss has halved in the last decade thanks to conservation policies, but the pace of destruction has not stopped. Since 2019, Brazil’s Amazon rainforest has been in the spotlight due to a series of fires and policy changes brought by president Jair Bolsanaro.

The History of Deforestation of Amazon

For most of human history, deforestation in the Amazon was primarily the product of subsistence farmers who cut down trees to produce crops for their families and local consumption. But since the 20th century, industrial activity and large-scale agriculture have greatly accelerated regional deforestation. Vast areas of rainforest were felled for cattle pasture and soy farms, drowned for dams, dug up for minerals and bulldozed for towns and colonization projects. At the same time, the proliferation of roads opened previously inaccessible forests to settlement by poor farmers, illegal logging, and land speculators. By the 2000s three-quarters of the Amazon had been cleared for grazing.

This situation was mitigated in Brazil starting in 2004 until the 2010s. Thank the increased law enforcement, satellite monitoring, pressure from environmentalists, private and public sector initiatives, new protected areas, and macroeconomic trends, the annual forest loss in Brazil that contains nearly two-thirds of the Amazon’s forest cover declined by roughly eighty percent.

Between August 2020 and July 2021, the rainforest lost 10,476 square kilometers, according to data released by Amazon, a Brazilian research institute that has been tracking the Amazon deforestation since 2008. The figure is 57% higher than in the previous year and is the worst since 2012.

Exhibit 1: Forest Cover in the Amazon Rainforest, 2020

Exhibit 2: Annual Forest Area Net Change, by Decade and Region, 1990-2020

The Fires in the Amazon

2019 was a destructive fire year that captured the world’s attention. An unprecedented number of fires raged throughout Brazil in 2019, intensifying in August. That month, the country’s National Institute for Space Research (INPE) reported that there were more than 80,000 fires, the most that it had ever recorded. It was a nearly 80% jump compared to the number of fires the country experienced over the same time period in 2018. More than half of those fires took place in the Amazon. While fires tore at the edges of the Amazon, many others sparked in the Pantanal, the world’s largest tropical wetland located south of the rainforest, which experienced its worst fires since at least 2002.

In 2020, fires again raged throughout the region. According to an analysis of satellite data from NASA’s Amazon dashboard, the 2020 fire season was actually more severe by some key measures. According to NASA, fire activity was up significantly in 2020. All types of fires contributed to the increase, including deforestation fires and understory fires, the most environmentally destructive types.

The fires have not stopped burning this year. They surge a new as cleared forest burns. Parts of Brazil and its typically lush rainforest are parched by drought and loaded with fire-kindling fuel after a surge of deforestation in 2020.

According to CNN, VOX and other media, most large fires in the Amazon are started by humans on recently cleared land. And deforestation for logging, mining and farming fragments the forest makes it more susceptible to catching fire on its edges.

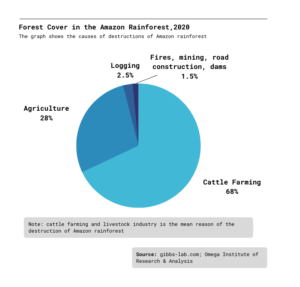

Pasture is the Main Reason

The impact of human activities is the main reason for the deforestation of the Amazon rainforest. Much of it was burned and cut down for cattle farming and agriculture. Extensive cattle ranching is the number one culprit of deforestation in virtually every Amazon country.

Brazil has 88% of the Amazon herd, followed by Peru and Bolivia. Alone, the deforestation caused by cattle ranching is responsible for the release of 340 million tons of carbon to the atmosphere every year, equivalent to 3.4% of current global emissions. Beyond forest conversion, cattle pastures increase the risk of fire and are a significant degrader of riparian and aquatic ecosystems, causing soil erosion, river siltation and contamination with organic matter. Trends indicate that livestock production is expanding in the Amazon. While grazing densities vary among livestock production systems and countries, extensive, low productivity, systems with less than one animal unit per hectare of pasture are the dominant form of cattle ranching in the Amazon.

Amazon Rainforest is Now a CO2 Source

The Amazon rainforest has long been an important part of the planet’s process of converting carbon dioxide into oxygen. While a recent study by the Monitoring of the Andean Amazon Project (MAAP) showed that Brazilian Amazon has been transformed from a carbon dioxide sink to a source for new emissions over the past two decades. While the Amazon as a whole, which straddles nine countries, has absorbed about 1.7 billion metric tons of CO2 equivalent more than it has emitted in the past 20 years, the Brazilian portion alone has emitted a net 3.6 billion metric tons during that period.

Exhibit 3: Forest Cover in the Amazon Rainforest, 2020

The Political Drives Behind

In fact, tree cover and primary forest areas in many of the South American countries included have been under great threat, especially in the last decade. The Amazon rainforest is a vast and difficult region to access. It is also an exceptionally socially diverse and impoverished part of Latin America, and current economic dynamics have increased the pressure on its natural resources. These problems are not confined to Brazil, but the size of Amazon and its political environment shift are the main cause of international accusations. Brazil’s efforts to protect the Amazon since 2004 are reflected in a gradual decline in annual forest loss. But this positive trend had been stopped since Jair Bolsonaro won the presidential election in 2016 and Brazil’s political landscape shifted to the right.

Capitalizing on the economic concerns of the electorate on the campaign trail, Bolsonaro promised to restore the economy by exploring Amazon’s economic potential. As a result, the deforestation rate raised after years of decline, and the powerful agricultural lobby in the Brazilian congress has been pushing for more development of the forest. That agricultural lobby endorsed Bolsonaro during his election campaign.

Recent changes in Brazil’s regulations have reportedly encouraged illegal extractive activities, which has incited a cycle of degradation and violence in the countryside, including recurrent invasions of indigenous reserves. About 13% of Brazil is legally designated as indigenous land, most of which is in the Amazon and reserved for the country’s 900,000 indigenous people (less than 0.5% of the population). Bolsonaro’s rule has undoubtedly challenged the survival of these protected areas and the indigenous population.

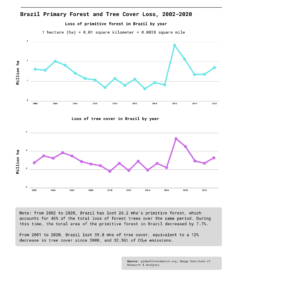

Exhibit 4: Brazil Primary Forest and Tree Cover Loss, 2002-2020

What Did We Get From COP26?

To avoid the deterioration of the condition in the Amazon rainforest meets the interest of all nine Amazonian countries. Brazil, along with other countries involved, is in need of new deforestation-free, sustainable development opportunities and economic diversification for local communities.

The good news for Brazil and Amazon was that Bolsonaro and the Colombian president, Ivan Duque, allied during the latter’s visit to Brazil, vowing to attend The 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP 26), the UN’s climate conference in Scotland that started on October 31, together, united by one goal: defending the Amazon.

During the COP26, more than 100 world leaders have promised to end and reverse deforestation by 2030 in the conference’s first major deal. Brazil was among the signatories. The pledge includes almost $19.2 billion of public and private funds. More than 30 of the world’s biggest financial companies, including Aviva, Schroders and Axa, have also promised to end investment in activities linked to deforestation. It is also very positive that it will try to reinforce the role of indigenous people in protecting their trees. Studies have shown that protecting the rights of native communities is one of the best ways of saving forested lands.

There are reasons to be cheerful about the proposed plan to limit deforestation, specifically the scale of the funding, and the key countries that are supporting the pledge. But there are significant challenges. Many previous plans haven’t achieved their goals. In fact, deforestation has increased since a similar pledge was launched in 2014. There are also major questions over how a major financial pledge could be effectively policed.

How to Make Change?

Facing these questions and challenges, the president of Brazil, governments and businesses need to work together to protect the rainforest while developing the economy. In terms of concrete strategies, there are a few to follow:

Connecting the Amazon rainforest’s economic policies with Brazilian climate goals

Brazil has made commitments to reduce carbon emissions and stop deforestation, but implementation is the key. Brazil could show the international community it takes the Amazon deforestation problem seriously by strengthening its action plans. It is critical for Brazil to maintain its current legislation to avoid the legalization of the deforestation levels seen today and halt illegal deforestation.Recovering degraded pasture

Brazil’s economy relies heavily on the livestock industry and agriculture, accounting for more than a quarter of GDP. According to the studies, violent reclamation is not necessary, instead, restoring degraded land could boost meat production. A 2020 WRI Brasil and New Climate Economy (NCE) study demonstrates the benefits this could bring. The hectares of degraded pastureland could lead to an increase of $3.7 billion in additional agricultural production, alongside $144 million in additional tax revenues from the agriculture sector alone.Attracting green investments

The international finance sector is quickly moving away from unsustainable investments and products. Over 1500 organizations globally (including over 1,340 companies with a market capitalization of $12.6 trillion and financial institutions responsible for assets of $150 trillion) have expressed their support on climate-related financial disclosures, which creates transparency around climate risks and sends out a strong signal to the countries seeking investment.Include local communities

The local communities depend on Amazon’s resources. While the current extraction-based economy does not benefit their well-being. Piloting and scaling new economic cycles that add value to both the preservation of the forest and to product value chains based on traditional knowledge such as acai and Brazil nut will be the key. The indigenous communities play a key role in the Amazon. It is essential to protect their rights. It would require coordination and modest investment but could lead to important social, environmental and economic benefits.The Amazon rainforest is the center of global climate projects and an important strategic location for environmental protection. Business and capital have the responsibility to pay attention to this and focus on sustainable development projects and investments to catalyze changes in Amazon’s situation.

Subscribe

Select topics and stay current with our latest insights

- Functions